Mission Possible: Addressing Health Disparities in Heart Disease and Stroke Outcomes

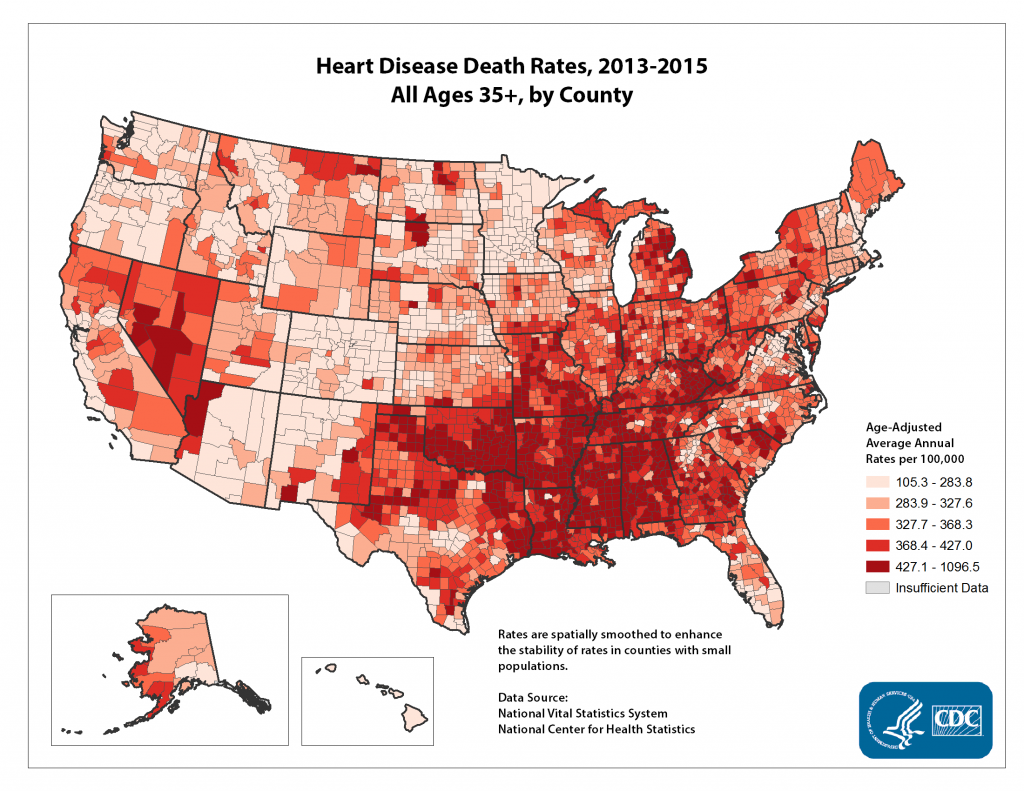

Posted on byAs the leading killer of Americans, heart disease and its associated behavioral causes are distributed throughout our country. Even so, some groups of people are more affected than others. Poverty and lack of education have long been associated with poorer health status and heart disease is no exception, occurring more frequently among people with lower incomes and less education. Racial and ethnic minorities, including African Americans and American Indians, whose histories in the United States are marked by severe trauma such as slavery, genocide, lack of human rights and loss of ancestral lands, and who today are often disadvantaged in terms of income and education, also experience higher rates of heart disease. Some geographic areas, such as the Southeast, Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta, places often characterized by poverty, lack of opportunity and low education, as well as lack of access to health care and community supports for healthy behaviors, also have higher rates of heart disease.

Public health as a discipline was established specifically to address historical, structural and other disadvantages that result in poor health status for some. Early public health successes establishing water and sanitation systems, housing and building codes, and pasteurization of milk and food safety regulations, as well as government programs such as public education, social security, Medicaid and a minimum wage, have all lifted up those most in need and contributed to improvements in health status for all.

Heart disease has been the leading killer of Americans since 1921, following advances in cigarette manufacturing and marketing, dramatically expanding access to the leading “actual” cause of death for Americans. While cigarette use emerged more widely in the 1910s and 1920s as a status symbol among the well-to-do, wide availability and two world wars rapidly expanded access. After conclusive evidence of the causal relationship between cigarette use and disease, many Americans quit smoking, with the risk factor more likely to affect those with less education and lower incomes. Today, tobacco use, poor diet and lack of physical activity continue to drive heart disease rates, while public health interventions to prevent and reduce tobacco use, improve nutrition, increase opportunities for physical activity and better control hypertension have been more successful in some populations compared to others, exacerbating disparities.

In 2013 the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) at CDC convened an internal Advancing Health Equity Call to Action meeting to initiate action to address the persistent challenges, as well as implement the recommendations that were made by the CDC Health Disparities Subcommittee in collaboration with the CDC Office of Minority Health and Health Equity. New and tailored activities were initiated both internally and externally with funded and unfunded partners in response to that meeting. For example, the Health Disparities Subcommittee recommends the usage of a dual strategy that includes national and locally determined interventions available to everyone as well as targeted interventions available to populations with specific needs. This dual approach was implemented in the CDC’s State and Local Public Health Actions to Prevent Obesity, Diabetes, and Heart Disease and Stroke cooperative agreement in 2014. In addition, training on Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping that CDC provides to state public health departments is an effective tool to locate populations with the highest burden of heart disease, and related conditions and risk factors.

Today, the public health enterprise continues to double down on support for populations most in need. Within NCCDPHP, the Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention is doing its part to address the health disparities in heart disease and stroke outcomes. In addition to primary prevention strategies, partnerships with health care payers and delivery, including with Medicaid and Federally Qualified Health Centers, help address gaps in access and treatment, particularly control of high blood pressure and high cholesterol. Better management and control of these risk factors can substantially reduce the risk of heart disease, heart attack and stroke. As heart disease mortality rates continue to decline, public health is ever mindful of the potential for gaps in health status to widen, for some to be left out of the overall progress, and the need to ensure that progress for the whole population includes every group within the population. Factors outside of traditional public health, such as the social environment, education, and economic opportunity, play an important role in the health outcomes. It is important that we identify and collaborate with a wide array of partners to address these upstream factors that shape health. When we work together with other sectors that influence health outcomes, we can build greater momentum to move the needle on the issues that have the largest impact on heart health.

Special thanks to Drs. Bauer and Thompson for contributing this blog in recognition of American Heart Month and as part of the celebration of the 30th anniversary commemoration of CDC’s Office of Minority Health and Health Equity. Our theme for the 30th anniversary commemoration is Mission: Possible. We believe “healthy lives for everyone” is possible and a goal that resonates in public health. Throughout 2018, we highlight success stories from the national centers, institutes, and offices at CDC that capture how they have improved minority health and reduced health disparities. We challenge our colleagues to become public health agents of change in their communities as well as at CDC.

Special thanks to Drs. Bauer and Thompson for contributing this blog in recognition of American Heart Month and as part of the celebration of the 30th anniversary commemoration of CDC’s Office of Minority Health and Health Equity. Our theme for the 30th anniversary commemoration is Mission: Possible. We believe “healthy lives for everyone” is possible and a goal that resonates in public health. Throughout 2018, we highlight success stories from the national centers, institutes, and offices at CDC that capture how they have improved minority health and reduced health disparities. We challenge our colleagues to become public health agents of change in their communities as well as at CDC.

What success stories do you know of in addressing and reducing health disparities in heart disease and stroke?

Posted on by