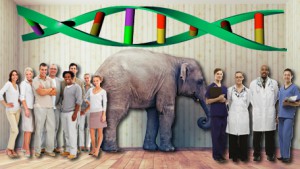

Precision Medicine and Population Health: Dealing With the Elephant in the Room

Posted on by In this week’s Journal of American Medical Association, we published a point-counterpoint commentary on the impact of precision medicine on population health. Announcement of the news of the US precision medicine initiative has been met with a range of responses from enthusiasm to skepticism about potential benefits, limitations and return on investment. In considering the potential contribution of precision medicine to health, we need to deal with the elephant in the room by asking a crucial question: will precision medicine improve population health? In May 2016, we had an online webinar point-counterpoint “debate” sponsored by the Precision Medicine and Population Health interest group at the National Cancer Institute. (The audio presentations and slides are available here.)

In this week’s Journal of American Medical Association, we published a point-counterpoint commentary on the impact of precision medicine on population health. Announcement of the news of the US precision medicine initiative has been met with a range of responses from enthusiasm to skepticism about potential benefits, limitations and return on investment. In considering the potential contribution of precision medicine to health, we need to deal with the elephant in the room by asking a crucial question: will precision medicine improve population health? In May 2016, we had an online webinar point-counterpoint “debate” sponsored by the Precision Medicine and Population Health interest group at the National Cancer Institute. (The audio presentations and slides are available here.)

After the debate, we laid out the arguments on both sides. We addressed the current tension between the enthusiasts and the naysayers, and hope to see an enhanced medicine-public health collaboration in the precision medicine era. Below is a brief summary of the arguments.

- Precision medicine might not improve population health because of the complexity of disease pathogenesis, especially for common chronic diseases. As a result, the promise of precision medicine to identify predictors of disease that can help guide personalized interventions may not be easily fulfilled. Changing behavior on the basis of genetic risk information to mitigate risks is difficult to achieve. The United States lags behind other high-income nations in population health status, and there are growing gaps between haves and have-nots in health. Solving these problems lies in addressing social, economic and structural drivers of population health, not in focusing more on individual health. Additionally, the precision medicine agenda could shift resources from other areas, and its appeal may lead to hype and premature expectations that may cause long-term disillusionment and erosion of public confidence in health sciences.

- Precision medicine might improve population health because we need both individual and public health approaches to improve health. Population health planning requires directing efficient use of resources toward those most at risk. Past successes of genomics and precision medicine indicate that they can yield population health benefit. For example, newborn screening is the largest “precision medicine” public health program in the world. Even with no new insights, near-term population health impact of precision medicine could accrue by implementing CDC’s evidence-based “tier 1” genomic applications that have evidence-based recommendations for their use and can benefits millions of people. Finally, new precision technologies and data science, over time, will improve our ability to track and prevent infectious disease outbreaks, measure environmental exposures, enhance disease tracking in populations and help develop policies and targeted interventions that can improve health and address health disparities.

Although these differences may seem irreconcilable, in many respects they represent a matter of emphasis. We suggest that the debate can be resolved by shifting the focus from the health of individuals versus the health of populations to strengthening medicine and public health partnerships that address health problems and disparities and capitalize on emerging data and new technologies, without neglecting well-recognized foundational drivers that are root causes of population health.

A major challenge ahead is figuring out how to best use large-scale data from multiple levels ranging from genomic to environmental information sources. Can these data help us better understand determinants of population health and interventions that will improve health outcomes in subpopulations? It is highly likely that interventions targeted to whole populations (e.g. policies, housing and education) and those tailored to higher risk groups will both be required to prevent disease, improve health and reduce health disparities.

We invite our readers to weigh in with thoughts and suggestions on the current and long term impact of precision medicine on the health of individuals and populations.

Please submit your comments below.

Posted on by